Who were the Africans who revolted aboard the Amistad?

Posted July 2nd, 2014 by James DeWolf PerryCategory: History Tags: Amistad, Cuba, Mende tribe, Sengbe Pieh

Today is the 175th anniversary of the Amistad revolt. In the United States, attention understandably focuses on the trial of the enslaved Africans who seized control of the ship from its crew, since the legal proceedings took place in this country.

Today is the 175th anniversary of the Amistad revolt. In the United States, attention understandably focuses on the trial of the enslaved Africans who seized control of the ship from its crew, since the legal proceedings took place in this country.

Yet who were the enslaved people who rose up and took command of the Amistad? Where had they come from, and where were they hoping to go?

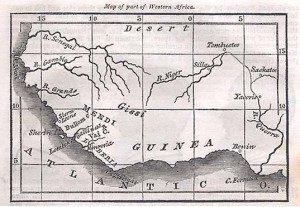

Those who revolted aboard the Amistad first met at Lomboko, an infamous fortress complex for the trading of slaves at the mouth of the Gallinas river along the west African coast, near the southern border of modern Sierra Leone.

Lomboko was run by a Spanish slave trader named Pedro Blanco, described as “the Rothschild of slavery.” As at other major slave trading posts, Blanco sought to manage a network of African leaders and merchants, arranging the buying and selling of enslaved Africans so that passing slave ships could quickly purchase human cargo and be on their way. The slave fort at Lomboko included barracoon which could house 5,000 enslaved people at any one time. ((Hugh Thomas, The Slave Trade: The Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade: 1440-1870 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997), 687.))

The leader of the Amistad revolt was Sengbe Pieh, who was also known by his Spanish name, Cinque. He was a member of the Mende people of West Africa, in what is now Sierra Leone and Liberia. ((http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/374734/Mende)) Sengbe reported later that he was born and raised in the village of Mani, a ten-day journey from Lomboko. He was seized in January 1839 when traveling alone by a group of four men from another tribe, and was sold to the son of an African leader who, in turn, sold him to the Spanish at Lomboko. All told, he spent about a month enslaved by Africans, and then another two months at Lomboko. Sengbe left behind a wife, two daughters, and a son, Gewaw, when he was forcibly taken into slavery.

The leader of the Amistad revolt was Sengbe Pieh, who was also known by his Spanish name, Cinque. He was a member of the Mende people of West Africa, in what is now Sierra Leone and Liberia. ((http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/374734/Mende)) Sengbe reported later that he was born and raised in the village of Mani, a ten-day journey from Lomboko. He was seized in January 1839 when traveling alone by a group of four men from another tribe, and was sold to the son of an African leader who, in turn, sold him to the Spanish at Lomboko. All told, he spent about a month enslaved by Africans, and then another two months at Lomboko. Sengbe left behind a wife, two daughters, and a son, Gewaw, when he was forcibly taken into slavery.

Sengbe’s second-in-command aboard the Amistad was  Gilabaru, whose name was generally reported in the press as Grabeau. Gilabaru, too, was a Mende. He, however, said that he was born deeper in the interior of west Africa, two months’ journey from the coast. Gilabaru’s uncle, he told investigators, had bought two slaves, which he used to pay off a debt; when one of the slaves ran away, Gilabaru was seized as compensation. He was sold to an African slave merchant, who in turn sold him to the Spanish at Lomboko. Gilabaru left behind a wife when he was enslaved.

Gilabaru, whose name was generally reported in the press as Grabeau. Gilabaru, too, was a Mende. He, however, said that he was born deeper in the interior of west Africa, two months’ journey from the coast. Gilabaru’s uncle, he told investigators, had bought two slaves, which he used to pay off a debt; when one of the slaves ran away, Gilabaru was seized as compensation. He was sold to an African slave merchant, who in turn sold him to the Spanish at Lomboko. Gilabaru left behind a wife when he was enslaved.

The other other enslaved Africans aboard the Amistad told similar stories of being enslaved and being sold, often months or years later, to the Spanish traders at Lomboko. Margru, for instance, was was a young girl whose father, she said, had given her as collateral for a debt; when he failed to pay the debt, she was sold into slavery. She left behind her parents, four sisters, and two brothers. Teme was another young girl; she was seized by a group of men who broke into her house at night, taking her, her brother, and her mother. She eventually arrived at Lomboko, but never saw her mother or brother again.

The other other enslaved Africans aboard the Amistad told similar stories of being enslaved and being sold, often months or years later, to the Spanish traders at Lomboko. Margru, for instance, was was a young girl whose father, she said, had given her as collateral for a debt; when he failed to pay the debt, she was sold into slavery. She left behind her parents, four sisters, and two brothers. Teme was another young girl; she was seized by a group of men who broke into her house at night, taking her, her brother, and her mother. She eventually arrived at Lomboko, but never saw her mother or brother again.

In April 1839, a Portuguese slave ship, Tecora, stopped at Lomboko and loaded about 600 enslaved Africans, including Sengbe and his fellow captives. They would later testify that they were kept naked during the crossing of the Middle Passage, chained into half-seated, half-lying positions, and whipped if they failed to eat. Those who died were tossed overboard into the ocean.

When the brig Tecora arrived in Cuba in June, those who had survived the passage were placed for sale in Havana’s slave market. After ten days, fifty-three of the Mende were sold to Pedro Montez and Jose Ruiz, Cuban plantation owners from the coastal town of Puerto Principe who planned to sell the Mende in the domestic slave trade.

On the night of June 28, 1839, Montez and Ruiz loaded the 53 enslaved Mende aboard the schooner Amistad and set sail from Havana, bound for Puerto Principe. There, they planned to sell all 53 to work on a Cuban sugar plantation.

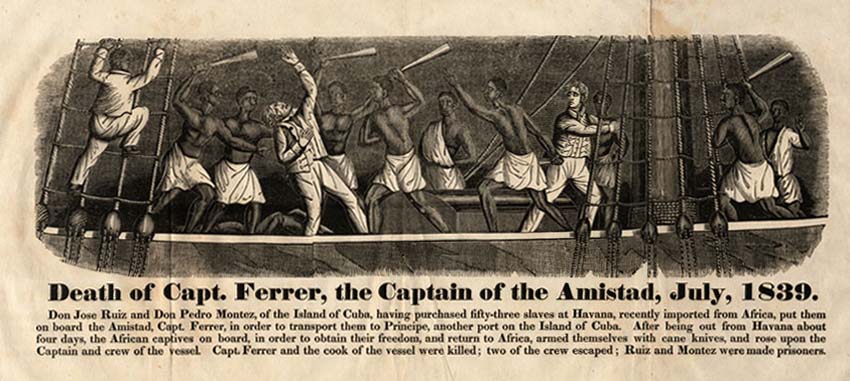

The rest of the story is relatively familiar: On the fourth night at sea, Sengbe and the other enslaved Mende freed themselves from their iron restraints and armed themselves with knives used for cutting sugar cane. Early on the morning of July 2, during a storm, they rose up and seized control of the ship. Aboard were five white people, a mulatto cook, and a black cabin boy. The mutineers killed the ship’s captain, Ramon Ferrer, and the cook, whom, they testified, had tormented them with tales of being fed to the Spanish when they reached Puerto Principe. Two of the crew fled in the ship’s boat, while the cabin boy was spared. Ruiz and Montez were kept alive to help navigate the ship.

Sengbe and the other newly freed Africans demanded that Montez, who had been a ship’s captain, sail the Amistad to Africa. Montez first claimed not to know the way to Africa, and then he deceived his captors, sailing slowly towards Africa by day, while steering for the United States by night. After six weeks, the Amistad reached Long Island, where the ship was seized and an inquiry began which led to the trial of those who had been enslaved aboard the Amistad.

Sources: Much of the information above about the individual Africans aboard the Amistad is taken from the their biographical sketches in John W. Barber, A History of the Amistad Captives (New Haven, Conn.: E.L. & J.W. Barber, 1840).

July 3rd, 2014 at 3:42 pm

Thank you, Tracing Center, for giving us a glimpse into our history and that of the 175th anniversary of the Amistad Revolt. We have never been taught our original history of our OriginaI Black People, while in grade school, only in college where too few of us attend. I have learned so much from this historical, insightful, chronicling of the Amistad uprising. I was once an invited guest, to a “pomp and circumstance” event, the dedication of the “Connecticut Register & Manual” being dedicated by the Connecticut Secretary of State, photographed with the current Captain of the Amistad, at an event he and the “Hartford Courant” cut the Captain out of the picture and only featured me and the 5 Generation Black History Family photograph, I am being held by a Slave who lived through Slavery and died at the sage age of 111, she was my Great, Great Grandmother…nnd when asked why they did this…they stated “the Slave and I were the bigger story” because the Slave didn’t escape Slavery.”. I shared this story because I agree with your comment that …”We hear so much about y the Schooner Amistad and very little about the Captives…I give them honor and respect but we must research and learn much more about the actual Slaves,such as the one holding me…her name was Charlotte McClee and I’m still trying to learn more about her as I trace her cabon footprints back to the plantation she was freed from and learn more about the unique lineage and “Roots” I was handed down. We must all seek to learn the truth about our past because as the British Royal Queen, ruling by bloodline, Queen Elizabeth said..”The Present is nothing Without the Past.” I believe the Jews, recalling their Holocaust and honoring their past, will, also, attest to this adage…but we, African Americans, have such a difficult time just keeping up with our “today” that our past is just that, past!! I believe, cult leader Jim Jones stated it best, …”Those who do Not learn from the Mistakes and Evils of the Past are Doomed to Repeat them..” Let us remember our ancestor’s past, honoring our “Roots” paid for with their lives, blood, sweat and tears… and be mindful…Never Again and towards that end….care for one another as we care for ourselves…this according to the teachings of Christ…”We have yet to become that “Village” I keep hearing so much about. The Africans aboard the Amistad, these captives knew this credo…”Together we Stand, Divided We Fall!”. As we begin celebrating this Country’s Independence Day, we must also be mindful that “We are still Not Free.”….Not Then and Not Now!! Happy 175th Anniversary to the Amistad and 4th of July….stella for the Slave

February 26th, 2021 at 1:44 am

The description about Amistad story was very informative. However, there is a serious anri-Swmitic phrase when comparing the Portuguese owner as the Rothschild of the slave trade. The connection of Jewish influence in OWNING the slave trade is erroneous and therfore a false slur against Jews. This phrase should be eliminated asap. I will be glad to refer this case to the Anti Defamation League and other civil rights groups if prompt action to correct this misdee isn’t accomplished.

March 21st, 2022 at 9:32 am

Thank you for offering this comment, Jerry. Certainly you're right that Jewish merchants did NOT dominate the transatlantic slave trade, as is often claimed, and baseless allegations that they did are anti-Semitic.

However, there is no such claim here. Instead, it is noted that a Spanish slave trader has been described as "the Rothschild of slavery." This is a claim that his influence in the slave trade was akin to the extraordinary success of the Rothschild family in international banking.

This would be like saying that a Hollywood producer is "the Bill Gates of movie making." It wouldn't imply that Gates is involved, at all, in movie making, but that the producer's prominence in movie making is similar to Gates' influence in the tech industry.

March 10th, 2024 at 12:12 am

Jews were heavily involved in slave trade

March 10th, 2024 at 10:35 am

There were Jewish slave traders, yes. But they were a tiny minority. The vast majority of European and American slave traders were Christian. So I have to question why you would mention Jewish slave traders here.