Lessons from the British commemoration of the abolition of the slave trade

Posted September 11th, 2012 by Kristin GallasCategory: Public History Tags: Abolition of the Slave Trade, Black agency, Emancipation Proclamation, Northern slavery, Sesquicentennial of the U.S. Civil War

Recently I was reading an essay by Geoffrey Cubitt, senior lecturer in history at the University of York (UK) and co-investigator of the “1807 Commemorated” project, which analyzed visitor responses to the Bicentenary of the 1807 Act of Abolition in British museums. ((The essay, along with others on international museums/commemorations of slavery and the slave trade, can be found in Politics of Memory: Making Slavery Visible in the Public Space edited by Ana Lucia Araujo.)) First of all, I want to acknowledge how amazing it was that the University of York spent two years studying how Britain commemorated, through exhibits, memorials, etc, the abolition of the slave trade. The team not only wanted to find out how the country remembered this history, but how visitors to these museums and memorials reacted to learning about this difficult time in the country’s past. The results of this study, chronicled in a separate volume titled Representing Enslavement and Abolition in Museums, shows an awesome feat of visitor studies and conclusions on how a country tries to remember what it spent so long trying to forget.

Recently I was reading an essay by Geoffrey Cubitt, senior lecturer in history at the University of York (UK) and co-investigator of the “1807 Commemorated” project, which analyzed visitor responses to the Bicentenary of the 1807 Act of Abolition in British museums. ((The essay, along with others on international museums/commemorations of slavery and the slave trade, can be found in Politics of Memory: Making Slavery Visible in the Public Space edited by Ana Lucia Araujo.)) First of all, I want to acknowledge how amazing it was that the University of York spent two years studying how Britain commemorated, through exhibits, memorials, etc, the abolition of the slave trade. The team not only wanted to find out how the country remembered this history, but how visitors to these museums and memorials reacted to learning about this difficult time in the country’s past. The results of this study, chronicled in a separate volume titled Representing Enslavement and Abolition in Museums, shows an awesome feat of visitor studies and conclusions on how a country tries to remember what it spent so long trying to forget.

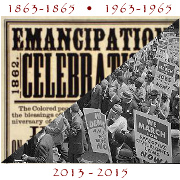

The lessons draw by Cubitt in his essay “Museums and Slavery in Britain” can serve as guide posts for the upcoming U.S. sesquicentennial commemoration of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Lesson #1 – Don’t forget to tell a comprehensive story. Commemorating the abolition of the slave trade or slavery isn’t just about the white people who fought in public forums and signed the official documents. It’s about years and years of the enslavement and degradation of people who consistently committed acts of agency on their own behalf – fighting for their freedom. We have to remember what and who was being emancipated by that particular document. We can no longer lay claim to our collective amnesia of a “slave country” – not just a southern “slave society” – and just remember the “happy” story of Lincoln signing the proclamation. As a country we need to share the multifaceted stories of the people who were enslaved, plus how and why Africans were enslaved in the United States.

Lesson #2 – It’s also about the deep ties of slavery to our country’s economic and political success throughout the 17th, 18th and early 19th centuries. We can no longer hide the fact that our great and wealthy country was built on the backs of enslaved Africans. From the cotton fields of the south to the textile mills of the north and provisioning plantations of the mid-west, all of America had a stake in the survival of the slave economy. Generations of Americans exempt themselves from the history of slavery. How many times have you heard someone say, “My people came after the Civil War. We had nothing to do with slavery.” Except they fail to remember that their ancestors were coming to a country whose success was due in no small part to the fortune of the slave economy.

Lesson #3 – Open up your museums/historic sites to participation from the whole community. Like many museums in the United States, those in Britain commemorating the bicentennial were primarily the domain of the “white and middle-class museum-going public.” ((Cubitt, p. 165.)) These same museums were now in the (often uncomfortable) position of having to persuade black members of their community that they could now “be places for the articulation of their voices, for the honest acknowledgement of their ancestors’ histories of suffering and achievement, and for recognition of their own entitlement as fill members of British society.” ((Ibid.)) Many British museums and historic sites approached the black folks in their communities, opened up channels of communication, and created opportunities for partnerships. This cannot be stated enough! An exhibit about black history must include black voices in order to draw a black audience.

Lesson #4 – Don’t forget the legacies! Often when humans commemorate dramatic historical events, we forget to remember that a particular story didn’t end with one event (a document signing, a cease fire, building of a memorial, etc). There are personal emotional and societal legacies that play out for years afterwards. In the case of slavery – the economic, legal, and social subjugation of black people in America didn’t end on January 1, 1863 or even April 9, 1865. We need to mark the subsequent 150 years of de jure and de facto segregation and discrimination faced by people of color in the United States.

Historic sites and museums should look closely at their themes, stories, primary documents, artifacts and other resources. We must as a public history community heed and apply the lessons from the Brits’ commemoration events. We must dig deep and wide to share a comprehensive and conscientious story of the emancipation of enslaved Africans in the United States. We must tell a comprehensive and conscientious story of slavery, its emancipation and legacies. We’re too intelligent a society to continue spinning myths and amnesia. We must remember in order to not forget.

December 23rd, 2014 at 1:33 am

I like your mission.

The history of African Americans is a history rich with political struggle. Whether we study the early slave rebellions, the Civil War, #reconstruction, Post-Reconstruction, the Garvey Movement, the 1960s Civil Rights and Black Power movements, or the rise of Black elected officials up to, and including, the election of Barak Obama, African Americans have engaged in deliberate political action to advance their quality of life within the United States. More posts relevant to African American history, enslavement, and struggle for self-determination and reparations can be found here: http://www.blackpolitics.org/